Phosphate Level Converter & Diagnostic Guide

Phosphate Level Converter

Convert between clinical phosphate units and assess your result against diagnostic thresholds for hypophosphatemia

Conversion Results

Clinical Significance:

Normal: 2.5-4.5 mg/dL (0.8-1.45 mmol/L)

Hypophosphatemia: Below 2.5 mg/dL (0.81 mmol/L)

When phosphate levels dive too low, the nervous system often sends warning signals. Muscle twitches, tingling toes, or even full‑blown weakness can trace back to a simple electrolyte imbalance.

What is hypophosphatemia?

Hypophosphatemia is a medical condition characterized by abnormally low concentrations of phosphate in the blood, typically defined as a serum phosphate level below 2.5mg/dL (0.81mmol/L). Phosphate is a vital mineral that supports bone health, energy production, and, crucially, nerve signaling.

Why phosphate matters for nerve function

Phosphate participates in the creation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the molecule that powers every nerve impulse. Without enough ATP, ion pumps in neuron membranes can’t maintain the electrical gradients needed for signal propagation. This leads to slower conduction speeds and, in severe cases, failure of the nerve to fire at all.

In technical terms, nerve conduction relies on the coordinated flow of sodium, potassium, and calcium ions. Phosphate indirectly regulates these ions by ensuring the energy supply for the Na⁺/K⁺‑ATPase pump. When the pump stalls, nerves become sluggish, manifesting as peripheral neuropathy or muscle cramps.

Symptoms that link low phosphate to nerve problems

- Peripheral tingling or “pins‑and‑needles” sensations, especially in the hands and feet.

- Gradual loss of strength in the lower limbs, sometimes described as “muscle fatigue” that doesn’t improve with rest.

- Reduced reflexes or delayed response during a neurological exam.

- In extreme cases, seizures or respiratory muscle weakness.

These signs overlap with other electrolyte disorders, but the combination of low serum phosphate and neuropathic complaints should raise suspicion of hypophosphatemia.

Common causes of hypophosphatemia

Understanding the root cause guides treatment. The most frequent drivers include:

- Refeeding syndrome - rapid nutritional rehabilitation after prolonged starvation, which drives phosphate into cells.

- Excessive urinary loss due to chronic kidney disease or diuretic use.

- Acute shifts of phosphate into cells during respiratory alkalosis (e.g., hyperventilation).

- Malabsorption syndromes such as celiac disease or after bariatric surgery.

- Rare genetic disorders affecting renal phosphate handling.

Diagnosing low phosphate and its impact on nerves

Blood work is the first step. A basic metabolic panel will reveal serum phosphate, while a full electrolyte panel can uncover accompanying abnormalities like low calcium or magnesium.

For patients with neurological symptoms, clinicians often add nerve conduction studies (NCS) or electromyography (EMG) to assess the functional consequences of the electrolyte deficit.

Key lab thresholds:

- Serum phosphate < 2.5mg/dL - diagnostic for hypophosphatemia.

- Serum calcium < 8.5mg/dL - may coexist and worsen neuromuscular excitability.

- Elevated alkaline phosphatase - can indicate bone turnover but not directly linked to nerve issues.

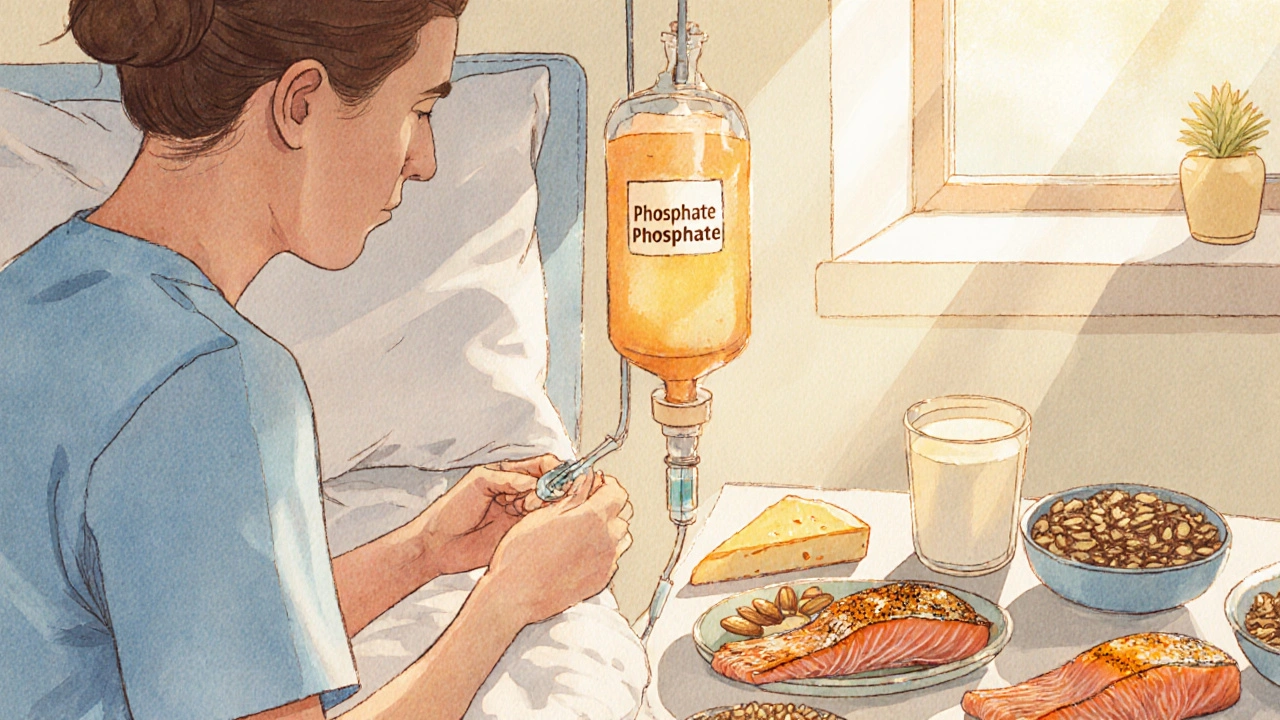

Management: Restoring phosphate to protect nerves

Treatment hinges on severity, underlying cause, and symptom burden.

- Oral phosphate supplementation - suitable for mild cases (serum 1.5-2.4mg/dL) and can be given as potassium phosphate tablets or liquid solutions.

- Intravenous phosphate - reserved for severe hypophosphatemia (<1.0mg/dL), especially when neurological deficits are progressing. Doses are carefully titrated to avoid overshoot, which can cause calcium precipitation.

- Address the primary cause: adjust refeeding protocols, switch diuretics, treat malabsorption, or correct vitamin D deficiency.

- Monitor electrolytes every 6‑12hours during IV therapy, and repeat nerve conduction studies after phosphate normalization to gauge recovery.

Lifestyle tips and prevention

Even after the acute episode resolves, maintaining adequate phosphate intake helps keep nerves happy.

- Include phosphate‑rich foods: dairy products, nuts, seeds, fish, and lean meats.

- Limit excessive caffeine or alcohol, which can increase urinary phosphate loss.

- If you’re on a high‑protein or low‑carb diet, check phosphate status regularly.

- Stay hydrated but avoid over‑diuresis without medical supervision.

Key Takeaways

- Phosphate is essential for ATP production; low levels directly impair nerve conduction.

- Neurological signs of hypophosphatemia include tingling, weakness, and delayed reflexes.

- Common triggers are refeeding syndrome, renal losses, and malabsorption.

- Diagnosis relies on serum phosphate measurement and, when needed, nerve conduction studies.

- Prompt oral or IV phosphate replacement, plus addressing the root cause, can reverse nerve dysfunction.

| Attribute | Normal (2.5‑4.5mg/dL) | Hypophosphatemia (<2.5mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy production (ATP) | Adequate | Reduced, leading to nerve fatigue |

| Typical symptoms | None | Tingling, muscle weakness, respiratory distress |

| Impact on nerve conduction | Normal speed | Slowed or blocked impulses |

| Common causes | Balanced diet, stable renal function | Refeeding, diuretics, CKD, malabsorption |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can low phosphate cause permanent nerve damage?

If identified early and treated, most nerve symptoms resolve completely. Prolonged severe hypophosphatemia, however, can lead to lasting neuropathy, especially in patients with other comorbidities.

How fast does phosphate level normalize after supplementation?

Oral phosphate usually raises serum levels within 24‑48hours. Intravenous administration can correct severe deficits within a few hours, but careful monitoring is essential.

Is it safe to take over‑the‑counter phosphate supplements?

OTC supplements are fine for mild, chronic low‑phosphate states, but they can cause gastrointestinal upset and interact with certain medications. Always discuss dosage with a healthcare provider.

What dietary sources provide the most phosphate?

Dairy (milk, cheese, yogurt), fish (salmon, sardines), meat, nuts, seeds, and whole grains are rich in bioavailable phosphate.

Should I be screened for phosphate levels if I have diabetes?

People with diabetes, especially if they have kidney involvement, are at higher risk for electrolyte disturbances. Periodic phosphate checks are advisable when kidney function declines.