Every time you pick up a prescription for a generic drug-like metformin for diabetes or lisinopril for high blood pressure-you’re holding the end result of a global, high-stakes supply chain. It’s not as simple as a factory making pills and shipping them to your local pharmacy. The journey from raw chemical to medicine bottle involves dozens of players, complex regulations, and financial layers most people never see. And yet, this system delivers 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. at a fraction of the cost of brand-name drugs.

Where It Starts: The Raw Materials

It begins with Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients, or APIs. These are the actual chemicals that make a drug work. For example, the API in generic atorvastatin is what lowers cholesterol. But here’s the twist: only about 12% of API manufacturing happens in the United States. The rest? Mostly in China and India. In fact, 88% of all APIs used in American medicines come from overseas. That’s not a coincidence-it’s economics. Labor and regulatory costs are lower there, and those countries have built massive, specialized manufacturing hubs over decades. But this global setup comes with risks. During the pandemic, when factories in India shut down or shipping slowed, over 170 generic drugs faced shortages in the U.S. The FDA stepped up inspections, going from 248 foreign facility checks in 2010 to 641 in 2022. Still, tracking quality across continents is tough. A single batch of API can be made in one country, processed in another, and packaged in a third before ever reaching a U.S. pharmacy.Getting Approved: The FDA’s Gatekeeping Role

You can’t just make a pill and sell it. Every generic drug must get approval through the FDA’s Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) process. Unlike brand drugs, which need full clinical trials, generics only need to prove they’re bioequivalent-meaning they work the same way in the body as the original. They don’t have to repeat expensive safety studies. That’s why generics cost so much less. But approval doesn’t mean easy production. Manufacturers must follow strict Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). That includes testing every batch for purity, potency, and stability. Even small deviations can lead to recalls. In 2023, the FDA flagged several Indian and Chinese plants for failing GMP standards. One misstep can knock a drug off the market for months.From Factory to Distributor: The Wholesale Middleman

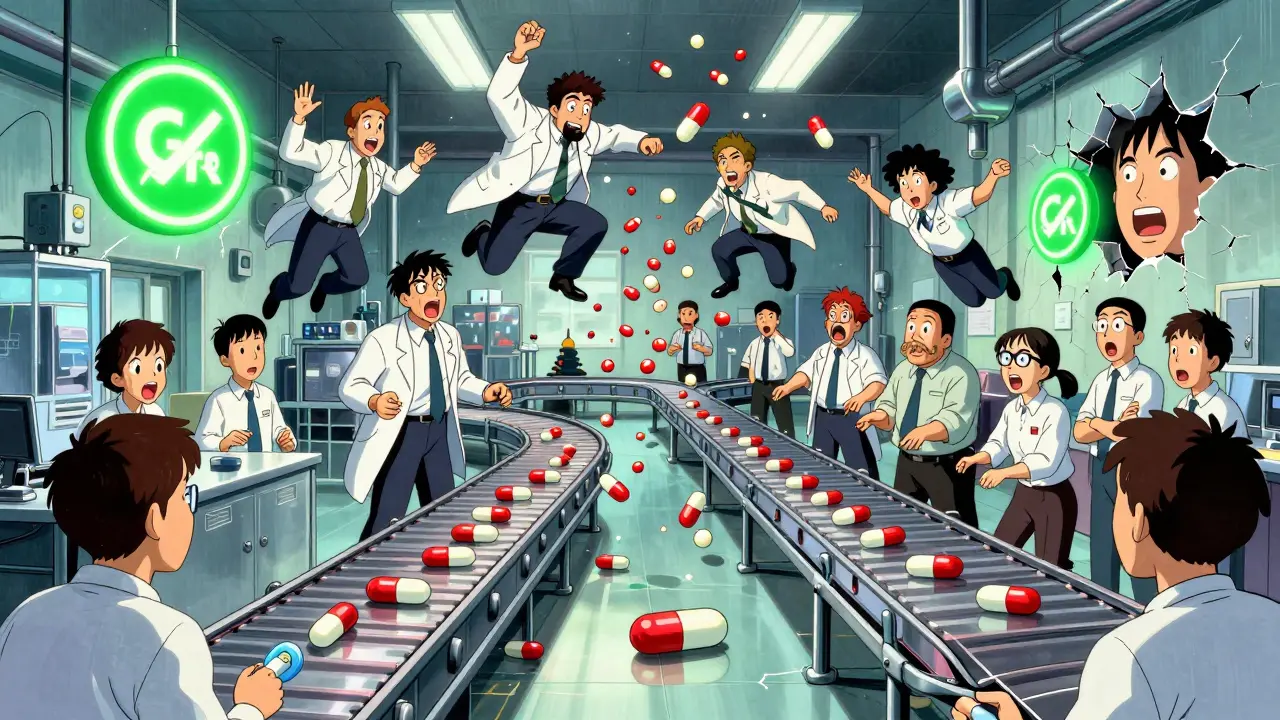

Once approved, the drug leaves the factory and heads to wholesale distributors. These aren’t small mom-and-pop shops-they’re massive companies like AmerisourceBergen, McKesson, and Cardinal Health. They buy drugs in bulk from manufacturers and then sell them to pharmacies. Here’s where pricing gets tricky. The price you see on the manufacturer’s invoice is called the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC). But pharmacies rarely pay that. Instead, they get a discount off WAC, often negotiated based on how much they buy. A big chain like CVS might get a 10% discount. A small independent pharmacy? Maybe 5%. That’s why bigger pharmacies can offer lower prices-they have more leverage. Distributors also offer "prompt payment discounts." If a pharmacy pays within 10 days instead of 30, they get an extra 1-2% off. It’s a cash-flow game. And because generics have thin margins, even small discounts matter.

How Pharmacies Get Paid: MAC and the PBM Maze

Now, the pharmacy has the drug. But how do they get paid for it? That’s where Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) come in. Three companies-CVS Caremark, OptumRX, and Express Scripts-control about 80% of the PBM market. They don’t sell drugs. They manage drug benefits for insurers and employers. PBMs set reimbursement rates using something called Maximum Allowable Cost, or MAC. This isn’t the price the pharmacy paid. It’s a government-style cap on how much the insurer will pay for each generic drug. For example, if the MAC for 10mg atorvastatin is $4, that’s all the pharmacy gets-even if they bought it for $5. That’s a problem. A 2023 survey by the American Pharmacists Association found that 68% of independent pharmacies say MAC rates are lower than what they pay to buy the drug. They lose money on every generic filled. Some pharmacies make up for it by charging higher dispensing fees, but that’s not always allowed. Others stop stocking certain generics altogether. And here’s the kicker: PBMs don’t negotiate with generic manufacturers. Unlike brand-name drug makers, who pay huge rebates to get on formularies, generic companies rarely play that game. Their prices are already low. So the pressure falls entirely on pharmacies to buy cheap and sell cheaper.Why Generic Drugs Cost So Little-And Why That’s a Problem

You might think the low price means the system is working perfectly. But look closer. According to the USC Schaeffer Center, generic manufacturers only keep 36% of the money spent on generic drugs. The rest? Goes to distributors, PBMs, pharmacies, and middlemen. Meanwhile, brand-name companies keep 76% of their spending. That’s not because generics are overpriced. It’s because the system is designed to squeeze manufacturers. When prices drop too low, companies stop making certain drugs. Why make a $0.10 pill when you can make a $20 heart medication? That’s why we see shortages of essential generics like digoxin or levothyroxine. Some manufacturers are trying to adapt. They’re using AI to predict demand, diversifying their API sources, and even using blockchain to track shipments. But these tools cost money-and small manufacturers don’t have it.

Who Benefits? Who Gets Left Behind?

The system works for patients: 90% of prescriptions are generics, and most cost under $10. It works for insurers and PBMs: they pay less. It works for big pharmacy chains: they have the scale to absorb losses. But it doesn’t work for small pharmacies. Or for patients who need a drug that’s suddenly unavailable. Or for the workers in overseas factories who produce the APIs under conditions few Americans ever see. The real cost of cheap generics isn’t just financial-it’s human. And it’s hidden.What’s Changing Now?

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 started to shift things. It caps insulin at $35 for Medicare patients-and it’s opening the door to more price transparency. The FDA’s 2023 Drug Competition Action Plan is pushing to speed up generic approvals and reduce shortages. Some states are now requiring PBMs to disclose their pricing structures. But the core problem remains: the system rewards volume and price cuts over stability. Until there’s a way to guarantee fair margins for manufacturers, shortages will keep happening. And when they do, it’s not the big players who suffer-it’s the patient who can’t get their blood pressure medicine.What You Can Do

If you rely on generics, here’s what matters:- Ask your pharmacist: "Is this the same as last time?" If the pill looks different, it’s likely from a new manufacturer.

- If a drug is out of stock, ask if there’s another generic version available. Not all generics are made the same.

- Use mail-order pharmacies or big chains if you’re on a fixed income-they often have better pricing.

- Report shortages to your pharmacist. The more people report them, the more attention they get from regulators.